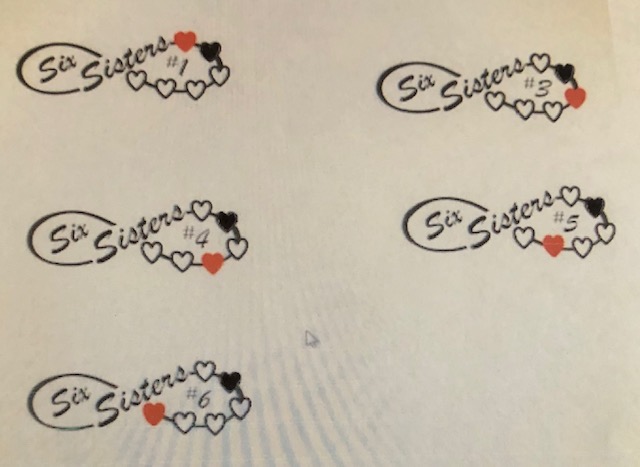

On Cilla Tucker’s left forearm is a tattoo that connects her with her five sisters.

Each of her sisters has the same tattoo, which is an infinity symbol with six hearts on the right loop.

The hearts are outlined, save for two. Each sister has a red one to show their place in the birth order and the second heart is filled black in memory of Beth, who was killed in the ‘60s after being hit by a car.

“After this COVID stuff calms down, we’re all gonna go in and get this heart filled in,” Cilla said, pointing to the last heart.

Their baby sister Bonnie Hunter, the sixth of six girls, was also the sixth COVID-19 death in Tipton County.

She succumbed to the virus on July 4.

“Being the baby sister, she’s a brat,” Cilla joked. “She is so much fun, she’s real outgoing.”

The vibrant blonde, who was set to turn 61 this year, loved her social circle, her sisters, her children and grandchildren.

She’d found love in a man named Gene Markwell, with whom she exchanged vows and rings but to whom she was never legally married.

Gene was there when Bonnie died, Cilla said.

“He’s a lineman and works out of town, mostly in rural areas. He’d been gone all week and came home on Friday and he was with her when she woke up Saturday morning and couldn’t breathe. I know he did CPR on her and everything, but it was to no avail.”

Her diagnosis

Last month Bonnie developed a cough, but it wasn’t the dry cough commonly associated with COVID-19.

She had a history of bronchitis and sinus infections, due to allergies. She went to the doctor the last week of June and was diagnosed with a bronchial infection and sinusitis.

“They also did a COVID test and that was, like, on a Tuesday. And on Friday she got the test results back and they were positive.”

Because she’d been diagnosed with other infections, and her cough was not typical of one commonly associated with COVID, Cilla suggests Bonnie didn’t believe she had the virus.

“It wasn’t so much like the dry cough that everybody talks about normally, so she went into self-isolation at that point. Prior to that she’d worked all week.”

Bonnie was the office manager at Edsal-Sandusky in Millington.

Her coworkers were tested and her best friend, who works with her, recovered after also testing positive.

Bonnie’s granddaughter, who’s 9, tested positive and had to quarantine from her mother, Ashley Ezell, and one-month-old baby brother. She was asymptomatic.

“She was with (Bonnie) for just a couple of hours one day before she got the test results back.”

And when Bonnie was diagnosed, she thought it’d likely just be a mild case. When her condition worsened, she refused to go to the hospital.

“No, she wasn’t going to the hospital … she’d be okay in a few days. She wasn’t going to the hospital.”

Cilla believes her sister was afraid to go to the hospital. Cilla’s son and husband and her sister Florence’s husband have all died in the hospital in recent years.

“It’s just a matter of more people go in the hospital and die than more people that don’t.”

Does she think, though, that Bonnie would still be living had she gone?

“It’s a good possibility. With the bronchitis to start with, and her lungs damaged, that takes away a lot of chances, but I think it would have been better had she gone than having not gone. And, personally, I wouldn’t want to go like that.”

‘She would not wear a mask’

It’s not known how Bonnie contracted COVID-19. She and Gene spent 10 days at an RV resort after Memorial Day, but it’s really hard to tell if that’s where it was.

“It could possibly be there or it would have had to have been some place in Millington, either at work or Morrie’s or Cheers or one of those places. They played shuffleboard at the different bars.”

Cilla said when the bars closed in the spring, Bonnie had friends come over to her house to throw darts. She was in and out of different businesses, too.

“Like I said, just very social. I don’t think she gave a thought about it. It was just in her nature to be with people.”

Cilla believes it cost Bonnie her life. She posted a message to Facebook urging people to take the precautions her sister did not.

“When I found out (she died), I was mad. I was mad at her all day,” she said. “She would not wear a mask. She hated them and said they made her claustrophobic. She didn’t socially distance. I don’t think she thought it was that big of a threat because nobody knows too much about it and, let’s face it, up in this area we’ve been very fortunate and we’ve had very few cases compared to Shelby County and New England.”

At the time of Bonnie’s death, there were only 633 cases in Tipton County, and the prison outbreak in Mason accounted for more than half of those.

Bonnie’s family members were the first in Tipton County to be open about their family member’s death.

“I think that a lot of people have the same mindset, that if you don’t know anybody that’s got it, it’s not a big deal. I think she could have prevented this had she put it in the right perspective. And that’s all I ask of anybody: think it through hard. This is not a joke. I personally think it’s going to get much worse before it gets better. The number of cases is just growing by leaps and bounds. We’ve gotta keep other people safe.”

Saying goodbye to Bonnie

Saturday morning, July 4, Bonnie told Gene she was having difficulty breathing.

“She apparently passed out and I know (Gene) did CPR waiting for the EMTs to get there. They never were able to revive her. They tried from the house all the way to the hospital and, finally, when they got there …”

Her daughter, Ashley, had been called and so were Cilla and the other sisters, Florence, Karen and Cathy.

Her cause of death was reportedly listed as cardiac arrest.

Other than infections diagnosed that week, Bonnie was healthy, Cilla said.

“She was the life of the party and we say she went out with a bang with fireworks on the Fourth of July.”

When asked if she thought Bonnie would choose to take precautions if given another chance, Cilla said she thought she would.

“Now I think she’d have that mask on and I think she’d cut back on socializing. She and her daughter Ashley were so close and she was close with her granddaughter … they spent a lot of time together. I think Ashley probably talked to her mother every day. She’s hurting and we’re all hurting.”

The outpouring of support through social media showed how loved Bonnie was.

She was cremated and the family plans to celebrate her life on Oct. 4, which is her birthday, but only if it’s safe to do so.

“We’re not doing a funeral, because Bonnie would have hated that. And we want to make sure it’s safer to do it, because we know there will be a lot of people there. She had so many friends.”

And, when it’s safe, four black hearts will reluctantly be filled in.

Cilla isn’t ready for it.

“You don’t expect to lose your baby sister to this. You just don’t.”

Leave a Reply