Since 1976, the month of February has been celebrated as Black History Month – an opportunity to dedicate an entire month to celebrating and educating Americans across the country and the world on the achievements and amazing accomplishments of Americans of African descent.

This year, we will celebrate Tipton Countians and their remarkable stories of perseverance and dedication, who, despite the obstacles and naysayers stacked against them, never gave up and worked hard to make their dreams come true.

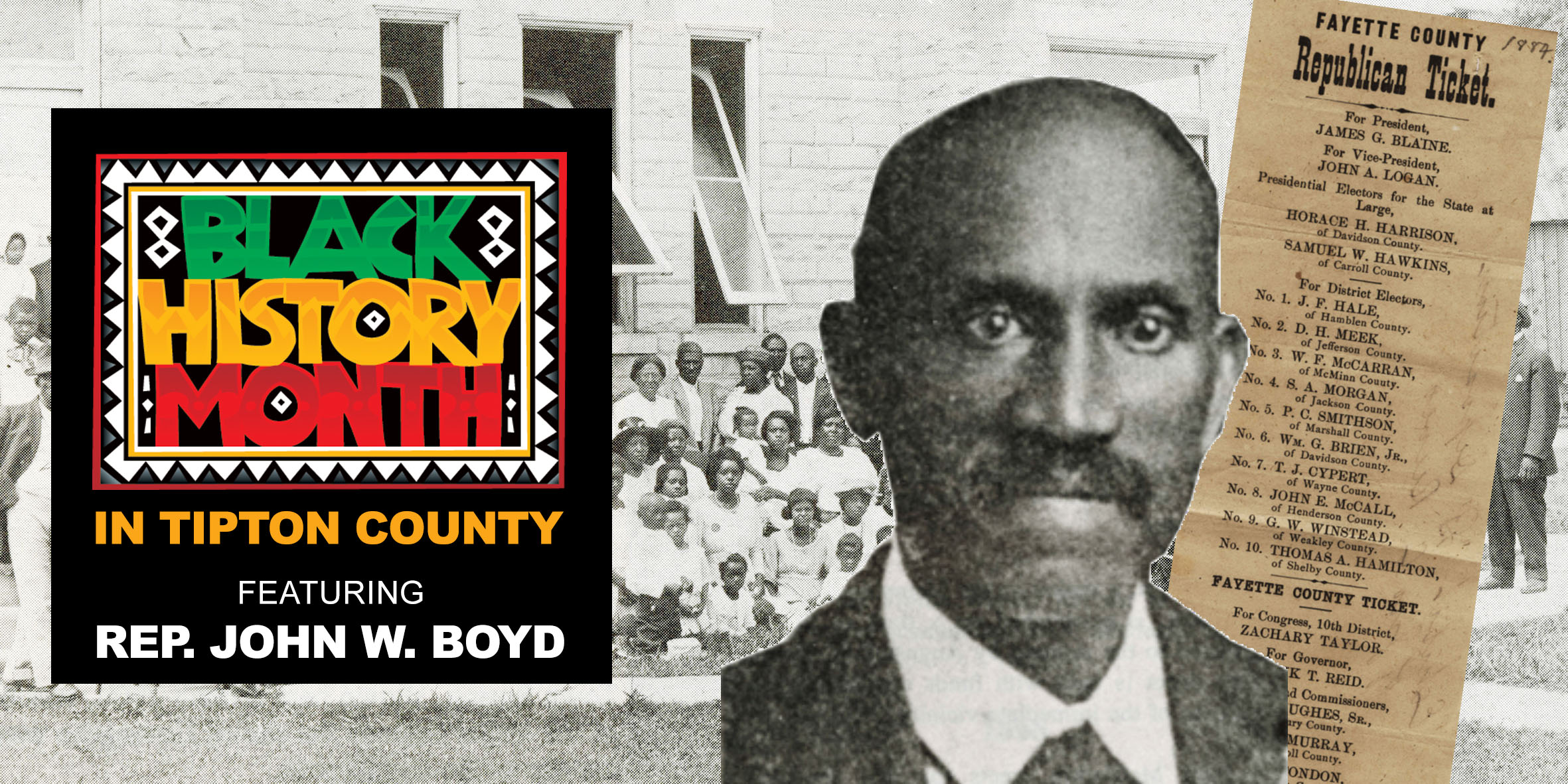

Tipton County native John W. Boyd was a former slave who became a respected attorney and magistrate in his hometown of Mason and served two terms representing Tipton County in the Tennessee House of Representatives in the 42nd and 43rd Tennessee General Assemblies from 1881 to 1884.

John William Boyd was born enslaved about 1852 in Tipton County to Philip and Sophia Fields Boyd, slaves on the Henry Sanford plantation who had moved with Sanford’s family from Orange County, Va. to Tennessee in the early days of Tipton County’s formation.

An intelligent young man, John W. Boyd lived and worked in Mason as a store clerk. Perhaps owning to a desire for more out of life, he applied and was admitted to the Covington Bar Association to practice law about 1870. Working as a lawyer and also as a magistrate, Boyd soon gained a reputation for fairness among county citizens and his political experience grew through his participation in county business.

Getting into politics

In 1876, Boyd was a delegate to the Republican State Convention held in Cincinnati, Ohio and he was selected as a representative from Tennessee’s Ninth District to the National Convention, playing a part in nominating Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio for president.

After the convention, Boyd was elected to his first six-year term on the county court in 1876, and re-elected in 1882 and 1888. After a short break, he returned to the court in 1897 to finish out another candidate’s unexpired term, and was once again elected in 1900 for his final six-year term. His years of magistrate service were well into the enactment period of Jim Crow laws and during a time when most black Americans were not able to win election to county or municipal positions.

Looking for greater responsibility and the opportunity to make a larger difference, John W. Boyd was elected to represent Tipton County for two terms in the Tennessee House of Representatives. From 1881-1882, he served in the 42nd General Assembly and from 1883 to 1884, the 43rd General Assembly.

It was during this period Boyd worked persistently with other African-American legislators to overturn Chapter 130 of the Acts of 1875, the first Jim Crow law enacted in the South, permitting racial discrimination in public facilities.

Two of Boyd’s bills were voted into law, one authorizing the governor to offer a reward for the arrest of a murderer, and one increasing the exemption from seizure or attachment in case of debt.

The latter bill was intended to protect poor families from having to sacrifice all their resources to repay a financial obligation. A third bill of Boyd’s, which made it illegal for railroads to discriminate against any passenger paying first-class fare, was amended to require racial segregation of passengers and was then adopted.

Appalled that his intentions had been so drastically distorted by the amendments, Boyd voted against his own bill, which soon became one of Tennessee’s Jim Crow laws.

The election of 1884

In the election of Nov. 4, 1884, having completed two terms in the House, John Boyd ran against Democratic attorney Houston Letcher Blackwell for an opportunity to represent Fayette and Tipton counties in the Tennessee Senate.

Blackwell, a Confederate veteran, was the former law partner of Democratic Congressman Charles Bryson Simonton of Covington, a member of the U.S. House from 1879-1883. The State certified Blackwell as the victor, so when he died unexpectedly on Jan. 2, 1885, three days before the 44th Session was to convene, Governor William B. Bate called for a new election on Jan. 20.

John P. Edmondson of Somerville took Blackwell’s place as the Democratic candidate against Republican Boyd. However, Boyd insisted that the second election was superfluous, since he was the rightful winner of the November election. Waiting in the Senate chamber from Jan. 5 until the end of the month, he challenged the original election results, arguing that he had been defrauded of his seat and should be sworn in.

According to Boyd, at some point during the Nov. 4 election, the District 4 ballot box had mysteriously “disappeared,” along with at least 400 Republican ballots – more than enough to give Boyd the victory. In his effort to contest the election results, he took depositions from the sheriff and several election officials, whose testimony indicated that two of the Democratic election judges had indeed taken the box away with them when they went to supper, later claiming that it had been “stolen and carried off.”

Despite such compelling evidence that the results of the original election were, in fact, invalid, the Senate nevertheless voted to seat Edmondson.

A disappointed John Boyd, who would have been Tennessee’s first black senator, returned to Tipton County. It would be another 84 years, actually 1969, before an African-American would be seated in the Tennessee State Senate.

Love and marriage

Boyd was married on March 13, 1879, to Martha C. “Mattie” Doggett in the Trinity Episcopal Church in Mason. Although, his wife was a member of St. Paul Episcopal Church, the local black Episcopal congregation, the couple actually married in the white church, with their wedding ceremony conducted by its priest, Rev. C. F. Collins. Their standing and appreciation throughout both the white and black communities allowed the Boyd family to freely attended services in both churches.

John and Mattie Boyd’s home for many years was in the town of Mason, just south of the railroad tracks on the east side of Main Street.

John’s brother Armistead married Mattie’s twin, Nannie. The two women were the daughters of Andrew Doggett, a free man of color who was notable in that he owned property before the Civil War, acquiring 200 acres more after the war ended.

John was the last African-American to hold the post of magistrate for decades.

Boyd, who outlived his wife, died on March 10, 1932, at about 80 years of age, and was buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Mason. The Tennessee Encyclopedia reports the couple had five children, however they left no surviving children.

The following is John’s obituary, found on the front page of the March 17, 1932, edition of The Covington Leader.

“WELL-KNOWN NEGRO BURIED AT MASON—John W. BOYD, a well-known negro of District #10, died suddenly of heart failure Thursday, March 10th. He was buried the following Sunday. There were no immediate survivors. Well up in the eighties in age, Boyd was politically prominent in the three decades following the Civil War. A resident of a district composed largely of negroes, he was for a number of years, magistrate for the 10th District, and following a split in the Democratic ranks in the years following 1880 was elected to the Legislature from this county. He was also a member of the Covington Bar.”

Based on the research of John W. Marshall, author of The Early History of Mason (1985) and Mason: A Glimpse into the Past (1991)

Update: In February 2020, the Tennessee House passed Resolution HR235 honoring Boyd’s memory and service. It was sponsored by current Tipton County Rep. Debra Moody.

Leave a Reply