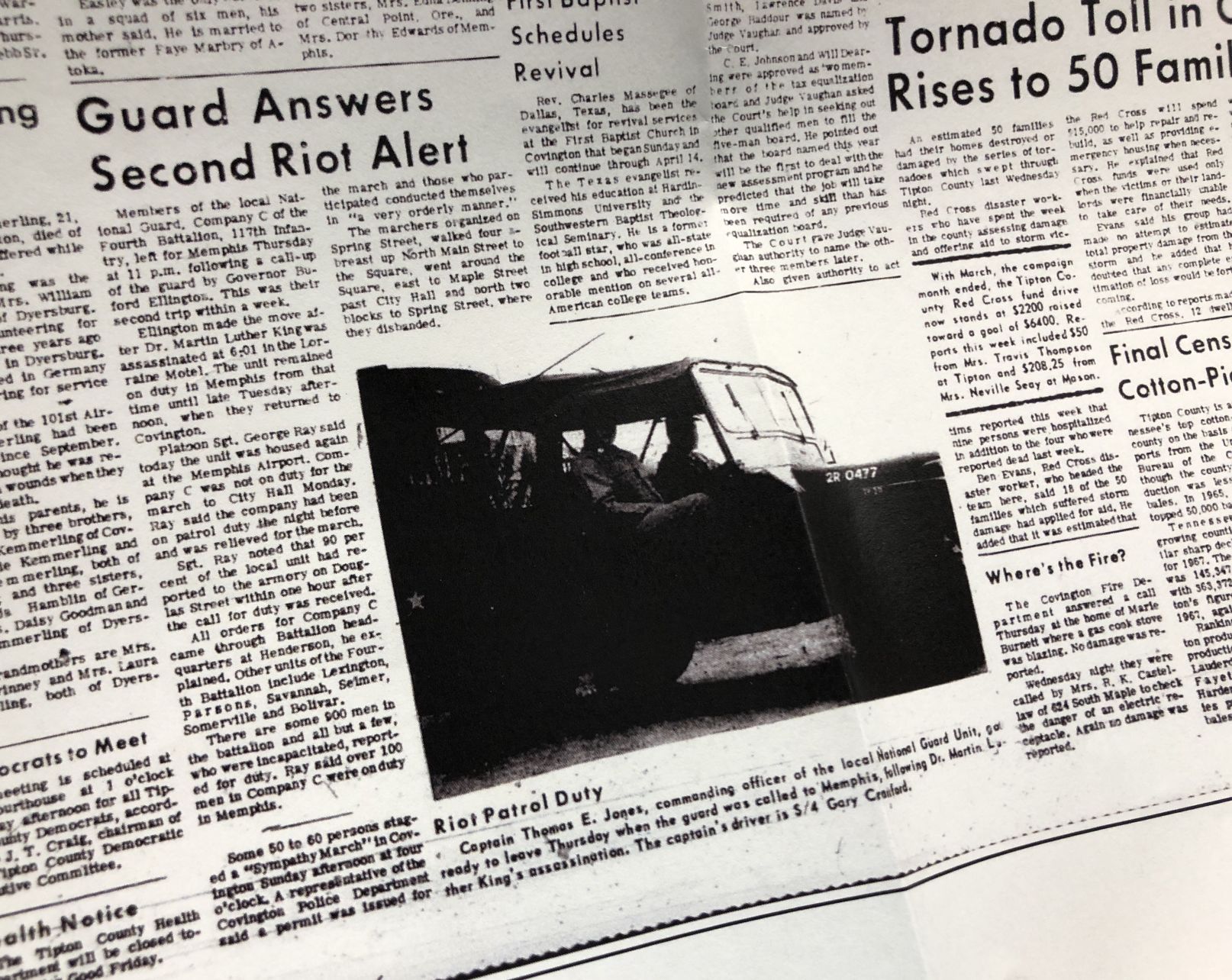

COVINGTON – It’s the day before the 50th anniversary of the shooting death of Martin Luther King Jr. and Minnie Bommer is looking at a reprint of the April 11, 1968 Covington Leader.

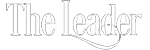

At the bottom of the page is a story about Covington’s unit of the Tennessee National Guard assisting with riot control in Memphis after King’s assassination.

The end of the story shares news of a sympathy march around the square attended by 50 or 60 people.

“I didn’t know they even printed that,” the alderwoman said. “I had no idea.”

Things were different in 1968, but Bommer said she was called a troublemaker even then.

An activist for most of her life, she is unapologetic about standing up for equality.

Like many other people, Bommer said she found out King had been shot from the television news.

“It was such a shame,” she said. “For everybody. It came across ‘Martin Luther King had been shot,’ pretty much the way you saw when Kennedy was shot … same kind of thing. They couldn’t find who did it at first.”

She pauses when asked what went through her mind when she heard the news.

“How do you answer that, you know? How do you answer that so somebody else will understand it? Shock. Rage. Anger. Resolve.”

Bommer, now in her late 70s, said it was local Civil Rights leaders Curtis French and Mack Edwards, the late father of alderman John Edwards, who filed the permit for the April 7, 1968 march.

“They would have gotten the permit, the rest of us were soldiers, if you will, of the march.”

When asked if she remembers the march, she gives a simple, yet complex, answer.

“Some things you don’t forget.”

Bommer wasn’t scared after King was killed, she was mad.

“You tried to keep it contained. That was always the thing – don’t let your anger show. For us, the march was to say that we were in sympathy with the family with what had happened to the family and with us, because our leader had died.”

The last 50 years

Reflecting on a half century of life since King’s death – a half century of fighting for equality, for representation, for progress, for inclusion, – Bommer said his death didn’t stop the movement.

“That’s what it was meant to do. It neither helped nor hurt … to me, it’s all part of a process. That’s the way I’ve always felt, that this was the time for this to happen and nothing could stop it. It still didn’t stop it.”

The local efforts fueled by the movement even changed Covington.

“At the time that he was killed, that’s when we resolved that we would get a seat in Covington. That was one of the things – no blacks were elected here in Covington.”

African-Americans only accounted for a third of the population then, she said, so electing a minority to the board, or most any elected office, didn’t happen.

Mack Edwards ran for office in the mid 1960s but wasn’t elected constable until 1972. He later served as alderman from 1989 until his death in 2005, but Bommer broke the barrier. She was the first African-American elected to the board in 1982, after the law regarding representation were changed.

Covington was split into three districts –thanks to a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union – and two aldermen represent each one.

Bommer and Edwards represent District 1, in which the majority of Covington’s African-American population lives.

Race relations in Tipton County have made progress, but there’s still a way to go, she said.

There’s no longer the threat of being ostracized or even dying for speaking out. Black history is now being told, their stories being inclued in the record.

Some of the efforts for equality haven’t been shared, though, and aren’t even discussed amongst family members. A lot of the struggles of the Jim Crow South have remained unspoken.

“You didn’t talk about it because it was really, really hard living through that kind of thing. Your children don’t understand why you didn’t say more or why you didn’t speak up or why you let them talk to you that way or treat you like that … they didn’t understand you could die. So you had to choose what things you would really stand up for because you could die.”

That note hits close to home for Edwards whose cousin, called Mack just as his father was, was killed in a house fire in a case of mistaken identity. The intended target was his father.

“They got the wrong Mack Edwards,” Bommer said. “That’s the kind of thing … it’s not something you want to talk about, but they need to know.”

“I think that’s when I would have had to quit,” added Edwards.

But his parents and other activists did not.

Bommer praised Mack’s tenacity during the Civil Rights movement.

“If there was something wrong around here, he was going to stand up for it,” she said.

That, on a basic level, is what the movement was about: equality and standing up for it.

It’s what Dr. King fought and died for.

These days, Bommer continues to fight for her constituents – be they white or black – and does so as one of the city’s leaders.

She is also one of the founding members of the Association for the Preservation of African-American History and Culture in Tipton County. The organization’s mission is to make sure Black history is recorded.

She realized Tuesday afternoon she’s the last one left of the group of Civil Rights activists who led marches to show solidarity in the King family’s grief and boycott segregated schools.

“I think I’m the only person left that was involved. See, there was Curtis and your dad …” she said, nodding her head and looking at John E. Edwards, son of former alderman and activist John Mack Edwards, “… and me and Mr. Mason … Benny Topps … Ms. Cleo and Mr. George … Rev. Smith … all of them are gone but me. Here I am. I’m the last one left.”

Leave a Reply