Luke Weathers III was an adult when he realized his father’s legacy needed to be shared.

He’d just started working and a friend introduced him as the son of Luke Weathers Jr., the famed Tuskegee Airman.

“He laughed and said there were no African-American pilots and it was then when I realized that people didn’t really know the truth.”

Weathers said he’s made it his mission to do presentations in schools, churches and anywhere else he and his wife can.

His father’s service, and the service of his fellow pilots, is an important piece of history. It’s history that is not being taught.

“We didn’t know the significance of it, to tell you the truth,” he said of his father’s service. “Being kids we didn’t learn about it in history books. They don’t talk about the Tuskegee Airmen. It was supposed to be a secret. This country didn’t want anyone to really know there were qualified African-American pilots fighting in the war, that there was a base in Africa completely run by African-Americans …”

Weathers said research presented to Congress at the time when his father served in the military showed African-Americans were physically inferior to their Caucasian counterparts.

“ … They don’t have the ability to operate complicated pieces of machinery, like airplanes,” he said, mimicking the Jim Crow era beliefs. “So, for them to go over and do what they did in World War II – which has not been surpassed or matched, by the way – no, this country didn’t want that out. They didn’t want that known. And it’s a shame that we’re supposed to be American citizens, but we’re not Americans.”

Weathers, a Drummonds native who shares he’s become more of a social activist as he ages, said he calls things as they are.

“I’m too old to play games anymore. I’ve been fortunate, I think I’ve lived a long life, but I’m at my point where I don’t bite my tongue. There’s so much about this country and historical facts that are distorted, either in the way of misleading or just outright lies … “

Weathers then discusses the Confederate flag and its history, sharing his frustration where misinformation is concerned.

“Our history, our true history, isn’t being told. This (exhibit) is one avenue we have of keeping not only my father’s story alive, but the Tuskegee Airmen story alive.”

Weathers Jr. was born in Grenada, Miss. to Luke Joseph Weathers Sr. and Jessie Rita Weathers. As a child, he remembered racist remarks about his mulatto grandfather and dark-skinned grandmother, Weathers III said.

“There’s racism, I guess, even within the races.”

Weathers Sr. was the first African-American to own a grocery store in Memphis, which happened after Weathers Jr.’s birth, and the building is still standing on Dunlap today.

Weathers Jr. moved to Memphis at age two and graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in 1939.

When he heard about the program in Tuskegee, Weathers Jr. asked the mayor for help becoming a cadet.

“Dad graduated from there in 1943, so he was only in the war for less than two years, but he accomplished so much.”

He flew 112 combat missions, said Weathers III, and shot down seven enemy aircraft – even two in one day.

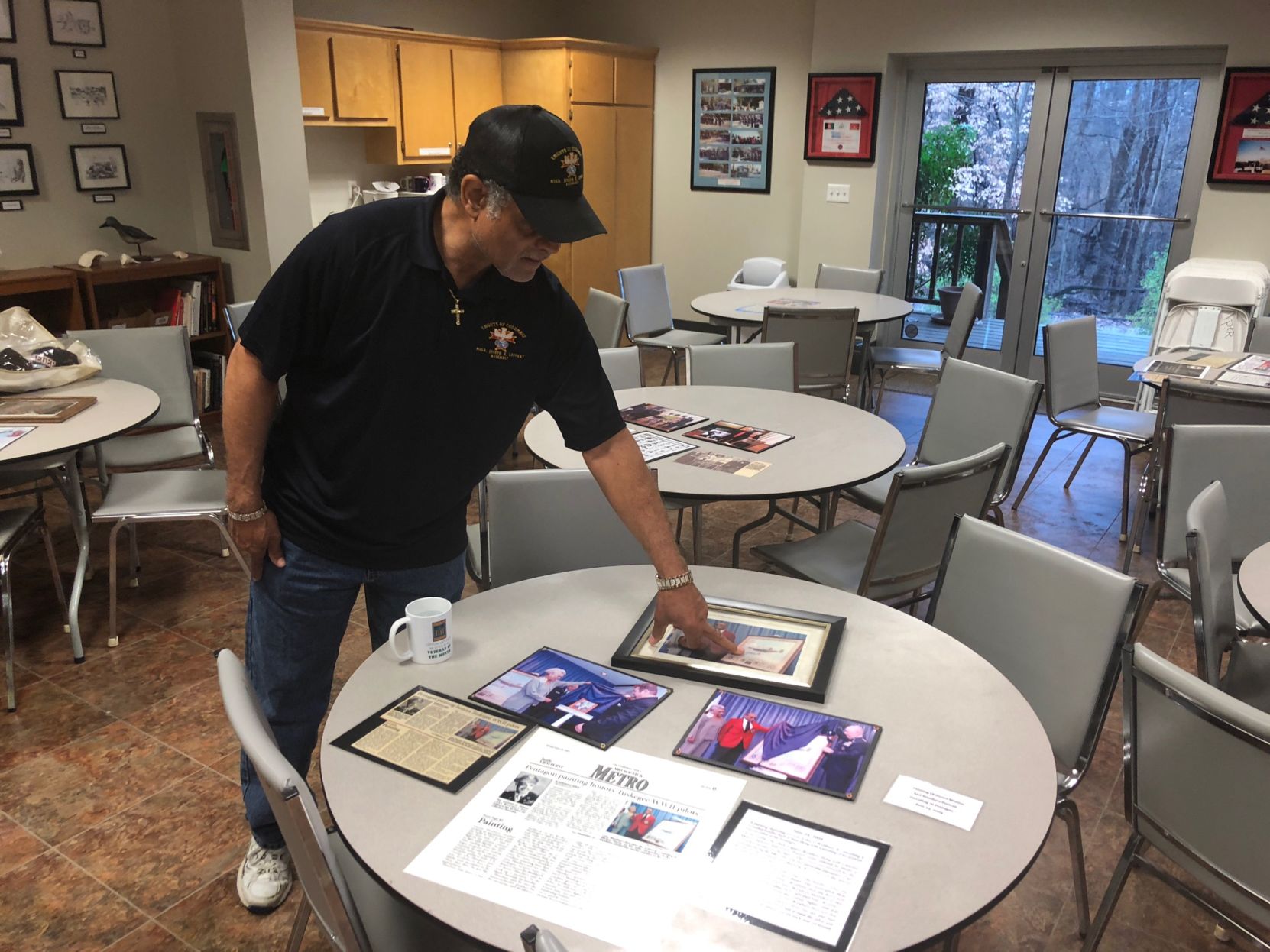

Weathers has collected a lot of memorabilia related to his father’s storied career.

There’s a painting depicting Weathers Jr. escorting a wounded bomber as well as a portrait of the lieutenant colonel, who died in 2011. Weathers III has collected stories and news clippings and photos, as well.

In one, 2,000 Memphis residents gathered downtown after raising money for the Spirit of Beale Street, the B-24 Liberator funded by $300,000 in donations collected by the African-American community for the purchase of war bonds.

The only Memphian to become a Tuskegee Airman, the city later named June 25, 1945 Captain Luke Weathers Day and he was honored with a parade down Beale Street to Handy Park.

He was also the first African-American to receive a key to the city.

The pilot received the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Flying Cross with seven clusters for the dozens of missions he flew over Europe and North Africa during the war.

He was honored with the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2007.

“It took 62 years for these guys to receive a medal they earned 62 years prior,” Weathers III said. “But it was against the law in this nation for an African-American to receive the highest honor. It was against the law, but it’s a fact and these are the things that our country doesn’t want to face … the reality of the injustices they have invoked and put on this country itself.”

Weathers III didn’t realize what a big deal his father was until he was an adult.

“He just didn’t talk about it. I never met a hero who talked about his heroism during the war. If you asked him if he was a Tuskegee Airman, he would just say, ‘Yes.’ Not until later in life, when he started getting accolades, did he ever start to share stories with us.”

These stories are what he hopes to share with local residents – like the children who populate the school right across the street from the museum – through the exhibit.

“They are our future and if we don’t treat our kids growing up and tell the truth and give them the avenues and the tools to make it, then generations are going to be lost to inequality. If it weren’t for inequality, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

The Red Tails exhibit – which borrows its name from the 332nd squadron’s nickname and the movie of the same name – opens Thursday.

“I think it’s great,” he said. “I think it’s an opportunity for us to keep his legacy going and that’s a great avenue for us.”

An opening reception will be held Thursday night at 5:30 and Weathers III will be the guest speaker.

The exhibit is expected to remain up into the spring.

General admission to the museum is free.

The museum is located at 752 Bert Johnston Avenue, Covington.

For more information about the museum, see covingtontn.com/tiptoncountymuseum.

Leave a Reply