Charleston natives Bill Jim Davis and his brother, Rob Roy, were stationed aboard the USS Helena when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

It started out as a regular day, Bill Jim has recalled.

“We were tied up at a dock there at Pearl Harbor and, normally on Sunday, there was a boy there at the dock who sold a Sunday paper,” he said in a video promoting Abandon Ship!, his memoirs of the day that lives in infamy and his time serving in the Navy during World War II. “So I bought a paper and went below deck to my living quarters four decks down.”

He said after awhile he heard an alarm. He and others thought it was crazy to hear a general alarm on a Sunday, but they nonchalantly made their way to their battle stations. Bill Jim’s was on the third deck.

“En route, there was a loud explosion shaking the entire ship, knocking me down. We started to run then.”

Not knowing what was going on, Bill Jim said he went topside to check it out.

“I could see smoke rising from the ship that’d already been torpedoed,” he said. “And then I noticed a Japanese plane float by. He tilted his wings just a little bit, apparently to see what damage he’d done, and I could see the red ball on the wings, so I knew the Japanese were attacking us.”

Roy was also serving aboard the Helena.

In a 2010 interview with The Leader, Bill Jim, who died in August 2018 at the age of 97, said his brother was preparing to go on shore at the time of the attack.

“There was no advance notice when (the Japanese) started bombing. None whatsoever. But we were in the war now.”

Just before 8 a.m., the USS Helena was struck by a single torpedo on its starboard side approximately in the center of the ship, the damaged area about 40 feet long. Instantly, he said, the ship was without steam and power. The explosion damaged the bulkhead between the forward engine and forward fire rooms, flooding both.

When he went topside, Bill Jim saw the Oklahoma on its side. The minelayer Oglala, tied up next to the Helena, was sinking.

He recounts the hours after the attack in Abandon Ship!, which was mostly written in 1979 at the encouragement of shipmates attending a reunion.

The second wave of attacks were focused on the battleship Nevada, aboard which their father served in World War I, but Bill Jim said this time the U.S. sailors were ready for the Japanese.

“Every anti-aircraft gun in the harbor opened fire. Consequently, very little damage was done. However, the Nevada was hit several times and forced aground near the harbor entrance.”

Though heavily damaged, he said the Helena needed to be at sea as it was “too tempting a target” while in port.

Powered by four steam-driven propellers, two were damaged by the torpedo and so the Helena would have to make do with only the other two.

The propellers needed steam, and after the aft room boilers were fired, water was entering from the flooded compartments. The boiler room crew had to compete to raise the steam pressure enough to power pumps to remove the water and the crew won, he said, with only minutes to spare.

Though the crew was ready to go underway by 9:30 a.m., there were still other problems, like the Oglala being jammed against the Helena and the need to shore-up the bulkheads.

Historical recounts of the incident credit the ship’s survival to its crew who quickly achieved watertight integrity, keeping the ship afloat and to its gunners who prevented the enemy from attacking the cruiser again.

On Dec. 7, 1941, more than 2,400 Americans died and 1,178 were wounded. Eighteen ships were sunk or run aground, including five battleships.

The Helena, Bill Jim reported, lost 29 men. Another 79 were wounded.

Between attacks, the officer-in-charge of the damage control unit, where he was stationed, asked for volunteers to help remove several dead bodies outside the forward engine room. Bill Jim said he did not volunteer.

“I have never forgotten the wide-eyed, terrified look on the face of one of these men,” he wrote. “He was on his hands and knees, seemingly still trying to escape but welded into that position by the fiery blast of the torpedo. Words cannot describe the tension, fear and anxiety we experienced during the remainder of the day. We had suffered devastating losses and expected more to come. No one knew the location of the attacking Japanese fleet, but we were convinced they would return for the kill … I felt trapped. The thoughts of becoming a prisoner-of-war were real. The night was even worse than the day. Everyone was mentally on edge.”

Two days later, the survivors were able to send Navy-provided postcards home. It was three weeks before his, addressed to Mr. Jesse H. Davis, arrived back in Stanton.

Joining the Navy

Bill Jim joined the Navy in 1938, well ahead of the war.

“I decided at the time when I graduated from high school I didn’t have any idea what I wanted to do,” he explained. “If you were going to go to college, you need to have some plans and I didn’t have any. So I thought the best thing was to join the Navy for four years and after that I’d know what I wanted to do. But little did I know I’d get caught.”

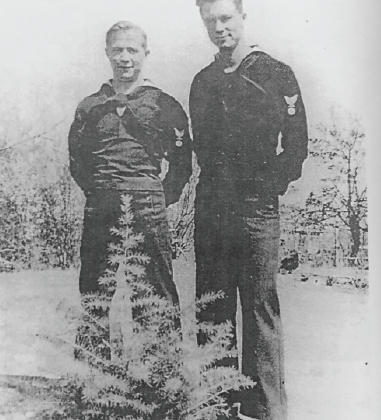

He reported to the newly-commissioned Helena (CL-50) on Sept. 28, 1939. Roy, who enlisted on Nov. 1, 1940, requested to be assigned to the light cruiser as well and boarded in August 1941.

The brothers served together in the electrical division and, in his book, Bill Jim said they became closer.

“It was good to have Roy with me,” he said. “Although we seldom went to liberty together. He was family and home.”

The brothers were allowed to serve together, as many did, because the Navy had a policy of assigning close family members together if requested. The policy was changed in November 1943 when the five Sullivan brothers lost their lives when their ship sank in the South Pacific.

While the ship was in the yard in Vallejo, Calif., the brothers went on leave and returned home where they were surprised to find out they’d become war heroes.

“We were treated like celebrities. We were the featured guests at the weekly luncheon meeting of the Covington Lions Club. I never considered myself a hero. I had only done my duty at Pearl Harbor, like thousands of others. Nothing but a miracle kept me out of harm’s way.”

War in the Pacific

After repairs were completed on the Helena it was sent back to the Pacific and to war.

The brothers Davis would become survivors of another attack on the Helena.

During the Battle of Guadalcanal, the crew, including the brothers, were instrumental in the saving the crew of the USS Wasp (CV-18) which was sunk by submarine torpedoes.

In early July 1943, Bill Jim found himself in the Kula Gulf, a waterway of the Solomon Islands and in a major battle between the Japanese and American forces. At approximately 3:08 a.m., the Helena was struck in succession by three Japanese torpedoes.

“When the ship was hit, my battle station was in the back of the ship and my brother’s was up front,” he said. “To me in the back of the ship, the first torpedo that hit sounded like it was a bump in road, like when you hit something when in a car. My brother was on this side of the bulkhead and it knocked off 120 feet of the bow. The Helena was 600 feet long and it knocked off a slash right there in front of him. The water was filling in and he had to wade to the main deck to get off the Helena. Then there were two more bumps. Two more torpedoes hit the ship and split it in two.”

Davis said he and his shipmates waited for permission to leave their battle stations and abandon ship.

“There was nothing to do back there,” he said. “We had to wait on orders to abandoned your battle station and the commander came up from the aft engine room and he told us we’d better get off. That’s when we went up to the main deck and the ship leaned over and I could see the ship separating. I had a life jacket on and I just stepped off into the water.”

Although both survived the sinking of the Helena, it was more than 30 days before each other learned the other had survived.

“I was in that water for about two to three hours before the destroyer [USS Nicholas] picked us up. But when the ship picked us up, the captain got on the line and said, ‘guys we gotta go, the (Japanese) are coming but we’ll send another ship to you.’ They left some boats in the water for them and they got in them and stayed the night on a Japanese-held island. My brother was one of them.”

Once they arrived back in San Francisco, Bill Jim said he had dozens of letters waiting on him and the ones from his parents were the toughest to read.

“(They) were the most touching and heart-breaking letters I have ever read. Tears streamed down my face as I read several of them. One of my dad’s – he never wrote, my mother did all of the writing – really got to me. He wrote, after hearing of the Helena sinking, ‘We prayed that at least one of our boys would survive, but after hearing from you, we wanted Roy safe too.’”

After the war

After the war, Bill Jim returned to live with his parents at 726 South Main Street and began working for a tobacco company in March 1946. He married Jean King in December 1946. The couple had two daughters, Billie Jean in November 1951 and Debbie in March 1953.

On Jan. 1, 1957, he was hired as a State Farm Insurance agent and his first office was on the west side of the square. The office moved to the Abernathy Building, on West Liberty, in 1959.

In 1969, he ended his military career after a dozen years active duty and nine years as a reserve.

He was elected to the state senate the following year, serving as an independent until 1982.

His wife, Jean, died in 1993 and he married Helen Oliver, to whom he is still married, in 1994.

Roy married the former Nadine Wilson of Garland in April 1945 and began working as civil service employee at NAS Millington. He later became a local merchant and owner of Davis Florist and Gifts.

Roy died in February 2005. Nadine survives him and, each year as the country commemorates the Pearl Harbor attacks, she celebrates a birthday.

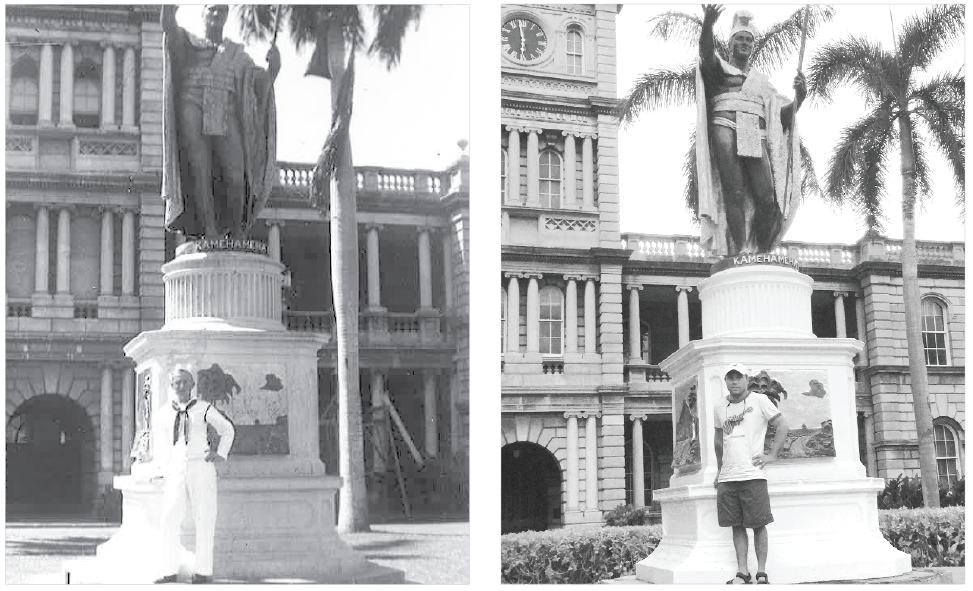

Roy’s grandson, Rob, recently traveled to Hawaii on his honeymoon and took his grandfather’s uniform with him, posing for photos in places where his grandfather once stood.

Writing the book

The book containing Bill Jim’s memoirs of Pearl Harbor and World War II was published in 2009.

He said he felt the need to write the book to ensure future generations understood and appreciated the sacrifices his generation went through.

“I wrote it way back yonder for my family and I thought now that the present generation knows very little about what went on back then,” he said in 2010 as the book was hitting shelves. “I wanted them to see what kind of life it was back then. It really was a very important time in the history of this world. With Nazi Germany and Pearl Harbor and the number of men who died. I thought they might enjoy reading about that time.”

He hoped younger generations understand how the world was changed because of Pearl Harbor and how different life might have been for Americans if we had not be forced into World War II.

“I hope they get a better understanding of the war and how it changed world history. Pearl Harbor changed history due to the fact that we were forced into the war. We had no option when you were attacked that way, America was unified like it had never been before. Germany was winning the war over there with England and if we hadn’t gotten in, there’s no telling where we would be now.”

Writing the book was not difficult for Davis once he was able to piece the memories back together again.

“It was an interesting experience for me then but I don’t think I could do it now,” said Davis. “I’m glad I did it then and it’s behind me. It did have a major impact on my life knowing how close I came to, well, I was really close to not making it at all. Life is really like that and I didn’t realize that because when you’re young you really just think you are invincible. But after that experience I could see so many men lost their lives at Pearl Harbor. I could see that life is fragile. Every day is a blessing and you’d better be thankful and try to do the very best you can to make life worthwhile for you and the people around you.

He said his years in the Navy were possibly the most important and, surely, the most eventful of his life.

“I had joined the Navy to primarily satisfy a desire to be of service to my country. Call it a love of country or patriotism, I was proud to be an American and, at the time, service in the military seemed the proper way to express this feeling.”

Sherri Onorati contributed to this story.

Leave a Reply