fourth generation of Edwardses to grow

up on Ripley Avenue in Covington.

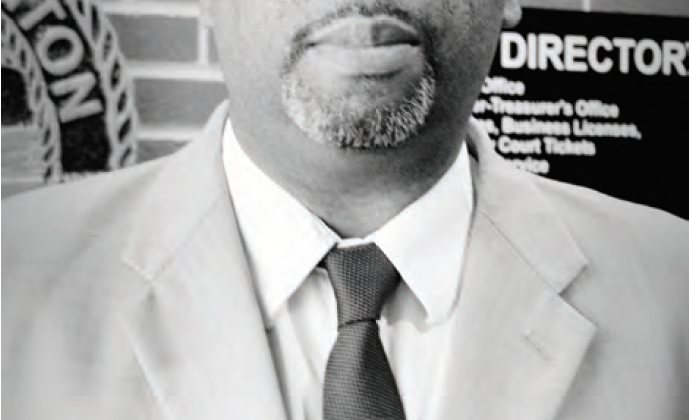

John Edwards relaxes in his seat, folding his hands in his lap while he thinks.

“Quincy Barlow, Minnie Bommer, Mayor David Gordon,” he says with a smile, now curling his thumb and forefinger around his chin while listing other people who’ve influenced him. “Jimmy Naifeh, Jeff Huffman, of course my parents …”

It’s a Tuesday afternoon and Edwards, who represents Covington’s District 1 as alderman and the city as vice mayor, has just attended back-to-back committee meetings. An action he proposed – the replacement of half-century old sewer lines at Frieze Hill while construction has them unearthed – was voted down, but he is still in good spirits.

“I just want to do the right thing,” he says.

That’s the only way he’s ever been taught.

Edwards, 50, is a lifelong resident of Covington. He’s lived on the same block, west of Highway 51 on Ripley Avenue, his entire life. He graduated from Covington High School in 1981 and has attended the University of Memphis and Dyersburg State Community College and has a diploma from the now former Tennessee Technology Center in Covington.

He is a C & C programmer at Delfield, a company that manufactures commercial food service equipment.

While his work at Delfield certainly doesn’t go unnoticed, it is for his community involvement and his family’s legacy that Edwards is known.

He has been on the Board of Mayor and Alderman for eight years, taking over after his father, John Mack Edwards, passed away in 2005.

“He asked me to take his term over if he wasn’t able to complete it,” the younger Edwards says. “I didn’t take it as seriously when he asked me, but he told me all about the issues that would concern me. I didn’t understand it then, but I was being taught at the time.”

And that’s how it often went with his father.

The elder Mr. Edwards was a steel worker and World War II veteran who served as a combat medic in the Rhineland, the Ardennes, Northern France and Central Europe. Very active in the Civil Rights Movement, in 1962 he was elected president of the Tipton County NAACP, a position he held for more than a quarter century.

It was during this time – before the younger Edwards was born – that a cousin named Mack Edwards died in a house fire Edwards calls mysterious. Even that didn’t stop his father from doing what he believed was the right thing for his community. (It did, however, stop him from making his son John Mack Edwards Jr.)

“It really means something when someone loses their life because of what you do and you still keep doing it,” Edwards says. “That taught me to be steadfast in my beliefs no matter what.”

Mr. Edwards once led the largest march of its kind from the Covington court square to the Tipton County Board of Education in support of integration and fair treatment.

Edwards and his siblings were enrolled at the all-white Covington Grammar School years before integration.

“Back then they bucked the trends,” he says of his parents. “We were only one percent of the class, but we didn’t have issues, we never saw any signs of racism. There were problems at the high school, but that was before I got there.”

When he was elected constable in 1972, Mr. Edwards was the first African-American to hold office in Tipton County since the early 1900s. He was elected alderman 17 years later in 1989 and was vice mayor when he died.

His wife, Alma Johnson Edwards, was the first African-American nurse at Baptist Memorial Hospital-Tipton.

Mr. and Mrs. Edwards were just doing what they believed was the right thing, and all along the way their son was learning.

“I look at the things my mom and dad went through because they refused to be treated like second-class citizens. They put their lives on the line. I can’t fill their shoes, but because of them I don’t have to go through that. I don’t have to make that journey because of what they accomplished.”

Involved with the Boys & Girls Club, Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) program and the Carl Perkins – Exchange Club Center for the Prevention of Child Abuse, Edwards said his mission is to do the right thing and leave his mark on his hometown.

“I want to make my neighborhood a better place to live,” he said. “So many people in my district have worked all their lives to buy houses and they’re afraid to sit on their front porches. We’re on the cusp of doing really successful things here, though. It’s very exciting.”

Leave a Reply