Today, many Americans take the act of voting for granted. It’s one of the most cherished and basic rights of citizenship as an American – the right to choose who governs and makes the laws that impact our daily lives.

But for many Black Americans who were born before 1947, this fundamental political right wasn’t always available to them.

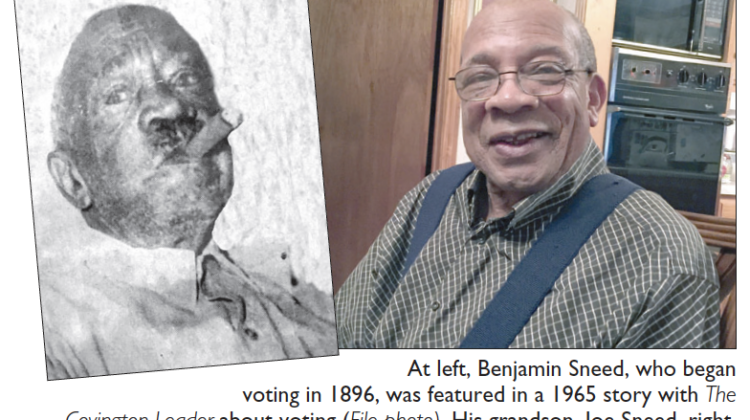

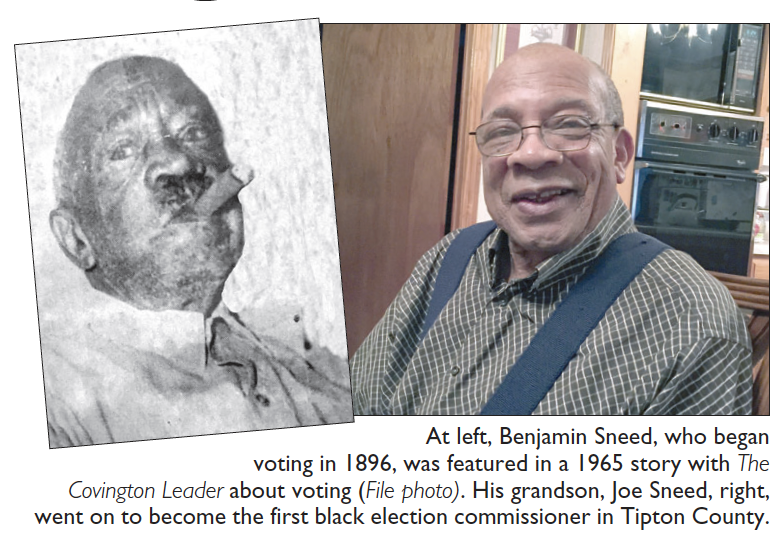

Tipton County Election Commissioner James L. “Joe” Sneed comes from a long line of proud voters and credits his grandfather and father for his start in politics. Because of them, Sneed has served 30 years as a Tipton County election commissioner

Sneed’s grandfather, Benjamin Sneed voted in his first election in 1896 at the age of 25, casting his ballot in the William McKinley-William Jennings Bryan contest for president of the United States.

According to a 1965 Covington Leader article, Benjamin, the son of enslaved parents, said he first decided to vote when “the white folks down here told me what a privilege it was to have a vote in the government,” and after marking that first ballot, he became a dedicated voter for the next 71 years, showing up at the Drummonds precinct for almost every county, state and national election.

Benjamin Sneed definitely had to face obstacles to exercise his right to vote, including having to walk more than three miles from his farm in Drummonds to reach the polling station, but that was the least of his worries.

Although, the Tennessee General Assembly granted black Americans the right to vote in February 1867 and the 15th Amendment approved by Congress two years later to the day, stated that “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” will not be used to bar U.S. male citizens from voting,” Black Americans still faced numerous government-sanctioned segregation laws designed to keep them from voting.

A variety of techniques – including literacy tests, poll taxes, intimidation, threats and violence were used to keep Black Americans from visiting the polls on Election Day.

Tennessee went a step further, failing to ratify the 15th Amendment until it was the last remaining state to do so in 1997.

It wasn’t until 1965, that the federal government finally stepped in and enacted the Voting Rights Act, giving all Americans the right to vote. The passing of the VRA is considered the most influential piece of legislation of the Civil Rights era, permanently barring barriers to political participation by racial and ethnic minorities and prohibiting any election practice that denies the right to vote on account of race – by the end of 1965, 250,000 new Black voters were registered.

Although, Benjamin, known as Papa Ben to his family, faced many challenges, he and other men of color paved the way so their descendants would one day enjoy the basic American right of suffrage.

Today, his grandson, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren benefit from his sacrifice today.

Benjamin’s legacy continues through his grandson, known throughout the county as “Joe.” He began his appointment as an election commissioner in 1985 after being called into the office of Judge Henry Vaughn. Vaughn, Tipton County’s County Executive at the time, asked Sneed to serve on the election commission. Sneed, who had been serving as a Tipton County constable for several years, remembers the conversation as if it happened yesterday.

“I got word that Judge Henry Vaughn wanted to see me,” recalled Sneed. “I didn’t know nothing about him then, except what I heard and that was everything he wanted he got,” he added laughing. “He said, ‘Joe, how’d you like to serve on the election commission?’ and I said, ‘Judge, it would be an honor.’ Just like that.”

Sneed’s years of service to Tipton County will amount to 30 years in May and for more than 25 of those years, he has been the only Black commissioner on the election commission. During that time, he’s seen Tipton County decrease from 21 precincts to today’s nine.

“I think I’ve only missed two meetings in 30 years,” said Sneed, justly proud of his record. “It was easy for me once I got there. I bring it to the churches. That’s the best way I can get out the message on the importance of voting,” Sneed says of his mission to educate the community on voting. “Eighty-five percent of the people in this county know me by name and I try to get to know everybody. I want everybody to know me. I make sure community members are aware [of voting procedures] to help the seniors and people.”

Sneed knows he’s able to help the community when it comes to the intricacies of voting because they trust him. Sneed’s many duties through the years, includes certifying elections, training poll workers and answering citizens questions.

“There ain’t no problem with me telling the truth,” he said. “You can tell the truth all the time. But you can’t lie all the time cause it’s going to catch up with you real quick.”

Sneed’s own relationship with voting began at the age of 18 in 1954 when he voted in his first election.

“I used to follow my father and cousin to the store on Wilkinson to watch them vote,” he recollected. “I started as soon as I turn 18 and I don’t think I’ve missed a time either.”

Even though Sneed started voting before the VRA was enacted, he said he didn’t struggle to vote in Tipton County. Unlike surrounding counties, Tipton County didn’t use literacy tests or poll taxes to prevent Black Americans from voting.

“I didn’t struggle to vote,” said Sneed. “I didn’t face any of that. I just had to show an ID card.”

Even though Tipton County didn’t have any barriers in place to prevent Black people from voting, there were questionable practices, including paying them to vote and handing out “cheat sheets” at the polls.

“My parents never talked about it,” he said shaking his head, “they never talked about it but back then, it was crooked. I’m going to tell you like it really was. It was really crooked then. They paid you to vote. You got $5 to go out and vote. They didn’t pinpoint you who to vote for but they had certain people who were giving out names.”

“You’d get a pint of whisky or $5 to vote,” added Bessie Sneed, Joe’s wife. “White folks was giving the Black folks money to vote for their candidates. But they couldn’t tell you who to vote for once you went in.”

“If you were intelligent enough, you voted for whoever you wanted to when you got inside,” added Sneed, laughing.

Sneed’s daughter, Dr. Charlotte Fisher remembers visiting the polls with her parents. “Even I remember people passing out money,” she said. “We’d be in the car and see that. You didn’t talk about it, but we knew that’s what they were doing.”

The Sneeds all agree that the money given out helped the rural community in which they lived, even though it was subtle intimidation.

“You have to remember the times back then,” said Fisher. “It was farm industry time and very rural. People back then were mostly sharecroppers, and $5 was a lot of money. They owed money and the white people then basically told them they better do this or you might not be able to take care of your family. It was a subtle harassment and it went on into the ’70s.”

“It helped out a whole lot,” said Bessie. “A lot of Black people working, they didn’t get $5 a day chopping.”

“You would get maybe $2.75 or $3 a day,” added Bessie. “You didn’t even get all of that, cause you had to eat lunch, so they would go get your lunch and you would have to pay them whatever they said you owed them. That was just the way it was. They would take that person around the corner to give them their money and for those folks, who couldn’t read, they would have that card and they would put the number on it of the person to vote for… that’s how they did it for the Black seniors. They told them, they had sheets and they would take those sheets in there with them.”

“And that happened because they weren’t educated on who the candidates were,” added Sneed. “Daddy always said, you vote but you got to know the candidate so you know who to vote for.”

Sneed said the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 helped the Black community in Tipton County a lot by getting more eligible voters to the polls.

“It really did help a lot,” he said. “At that time, 90-100 percent [eligible Black voters] got out to vote. It was just that simple. When they knew they could vote, they went out and voted.”

Sneed’s dedication to voting came from both his grandfather and his father, Sollie Sneed.

“Daddy, he just knew it was important to vote even though he only went to the third or fourth grade in school,” he said. “He just knew it was important for us to know how to work, vote and make an honest living. He wanted us to make an honest living working.”

Leading by example, Sneed has passed on that same intensity and dedication for voting, that began with Papa Ben, to his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“We always seen him involved,” said Fisher. “He didn’t try to force us in any way, he just talked about the importance of voting, to make your vote count. Even now, he asks grandkids when they turn 18, ‘Are you registered to vote?’ And makes sure they fill out their voter registration card.”

When asked why he’s stayed with the election commission for 30 years, Sneed’s response is simple.

“It was a good place for me to be,” he said matter-of-factly. “I was the only Black leader in Tipton County on the Election Commission and I could make a difference.”

But like all good things, Sneed’s time on the Election Commission is coming to an end. He said he’s ready to retire and will do so in May.

“I’m going to quit,” he revealed. “I’m not going to quit all the way, so that they still know me and talk to me, but I’m going to quit. Someone’s going to take over in the next three or four months ‘cause I’m coming out in May.”

And what would Papa Ben think of the strides his family has made that began with his casting his first ballot in 1896?

“I think he’d be mighty proud of us,” said Fisher, Papa Ben’s great-granddaughter. “He’d praised God that his living was not in vain; that he paved the way for all of us.”

Leave a Reply